As my last post started to explore, different types of dietary fats have different effects on the progression of alcoholic liver disease. This post will further explore the protective effects of saturated fats in the liver.

For many, the phrase “heart healthy whole grains” rolls off the tongue just as easily as “artery clogging saturated fats”. Yet where is the evidence for these claims? In the past few decades saturated fats have been demonized, without significant evidence to suggest that natural saturated fats cause disease (outside of a few well touted epidemiological studies). Indeed, most of the hypothesis-driven science behind the demonization of saturated fats is flawed by the conflation of saturated fats with artificial trans fats (a la partially hydrogenated soybean oil).

In the face of a lack of any significant scientific evidence that clearly shows that unadulterated-saturated fats play a significant role in heart disease (and without a reasonable mechanism suggesting why they might), I think the fear-mongering “artery clogging” accusations against saturated fats should be dropped. On the contrary, there is significant evidence that saturated fats are actually a health promoting dietary agent- all be it in another (though incredibly important) organ.

Again (from my last post), here is a quick primer on lipids (skip it if you’re already a pro). For the purpose of this post, there are two important ways to classify fatty acids. The first is length. Here I will discuss both medium chain fatty acids (MCFA), which are 6-12 carbons long, and long chain fatty acids (LCFA), which are greater than 12 carbons in length (usually 14-22; most have 18). Secondly, fatty acids can have varying amounts of saturation (how many hydrogens are bound to the carbons). A fatty acid that has the maximal number of hydrogens is a saturated fatty acid (SAFA), while one lacking two of this full complement, has a single double bond and is called monounsaturated (MUFA) while one lacking more (four, six, eight etc.) has more double bonds (two, three, four, etc.) and is called a polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA).

Next time you eat a good fatty (preferably grass-fed) steak, or relish something cooked in coconut or palm oil, I hope you will feel good about the benefits you are giving your liver, rather than some ill-placed guilt about what others say you are doing to your arteries. From now on, I hope you think of saturated fats as “liver saving (and also intestine preserving) lipids”. Here’s why:

In 1985, a multi-national study showed that increased SAFA consumption was inversely correlated with the development of liver cirrhosis, while PUFA consumption was positively correlated with cirrhosis [1]. You might think it is a bit rich that I blasted the epidemiological SAFA-heart disease connection and then embrace the SAFA-liver love connection, but the proof is in the pudding- or in this case the experiments that first recreated this phenomenon in the lab, and then offered evidence for a mechanism (or in this case many mechanisms) for the benefits of SAFA.

The first significant piece of support for SAFA consumption came in 1989, when it was shown in a rat model that animals fed an alcohol-containing diet with 25% of the calories from tallow (beef fat, which by their analysis is 78.9% SAFA, 20% MUFA, and 1% PUFA) developed none of the features of alcoholic liver disease, while those fed an alcohol-containing diet with 25% of the calories from corn oil (which by their analysis is 19.6% SAFA, 23.6% MUFA, and 56.9% PUFA) developed severe fatty liver disease [2].

More recent studies have somewhat complicated the picture by feeding a saturated fatty-acid diet that combines beef tallow with MCT (medium chain triglycerides- the triglyceride version of MCFAs). This creates a diet that is more highly saturated than a diet reliant on pure-tallow, but it complicates the picture as MCFA are significantly different from LCFA in how they are absorbed and metabolized. MCFA also lead to different cellular responses (such as altered gene transcription and protein translation). Nonetheless, these diets are useful for those further exploring the role of dietary SAFA in health and disease.

These more recent studies continue to show the protective effects of SAFA, as well as offer evidence for the mechanisms by which SAFA are protective.

Before we explore the mechanisms, here is a bit more evidence that SAFAs are ‘liver saving’.

A 2004 paper by Ronis et al confirmed that increased SAFA content in the diet decreased the pathology of fatty liver disease in rats, including decreased steatosis (fat accumulation), decreased inflammation, and decreased necrosis. Increasing dietary SAFA also protected against increased serum ALT (alanine transaminase), an enzymatic marker of liver damage that is seen with alcohol consumption [3]. These findings were confirmed in a 2012 paper studying alcohol-fed mice. Furthermore, these researchers showed that SAFA consumption protected against an alcohol-induced increase in liver triglycerides [4]. Impressively, dietary SAFA (this time as MCT or palm-oil) can even reverse inflammatory and fibrotic changes in rat livers in the face of continued alcohol consumption [5].

But how does this all happen?

Before I can explain how SAFA protect against alcoholic liver disease, it is important to understand the pathogenesis of ALD. Alas, as I briefly discussed in my last post, there are a number of mechanisms by which disease occurs, and the relative importance of each mechanism varies based on factors such as the style of consumption (binge or chronic) and confounding dietary and environmental factors (and in animals models, the mechanism of dosing). SAFA is protective against a number of mechanisms of disease progression- I’ll expound on those that are currently known.

In my opinion, the most interesting (and perhaps most important) aspect of this story starts outside the liver, in the intestines.

In a perfect (healthy) world, the cells of the intestine are held together by a number of proteins that together make sure that what’s inside the intestines stays in the lumen of the intestine, with nutrients and minerals making their way into the blood by passing through the cells instead of around them. Unfortunately, this is not a perfect world, and many factors have been shown to cause a dysfunction of the proteins gluing the cells together, leading to the infamous “leaky gut”. (I feel it is only fair to admit that when I first heard about “leaky gut” my response was “hah- yeah right”. Needless to say, mountains of peer-reviewed evidence have made me believe this is a very real phenomenon).

Intestinal permeability can be assessed in a number of ways. One way is to administer a pair of molecular probes (there are a number of types, but usually a monosaccharide and a disaccharide), one which is normally absorbed across the intestinal lining and one that is not. In a healthy gut, you would only see the urinary excretion of the absorbable probe, while in a leaky gut you would see both [6]. Alternatively, you can look in the blood for compounds such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS-a product of the bacteria that live in the intestine) in the blood. (Personally, I would love to see some test for intestinal permeation become a diagnostic test available to clinicians.)

Increased levels of LPS have been found in patients with different stages of alcoholic disease, and are also seen in animal models of alcoholic liver disease. Increased levels of this compound have been associated with an increased inflammatory reaction that leads to disease progression. Experimental models that combine alcohol consumption and PUFA show a marked increase in plasma LPS, while diets high in SAFA do not.

But why? (Warning- things get increasingly “sciencey” at this point. For those less interested in the nitty-gritty, please skip forward to my conclusions)

Cells from the small intestine of mice maintained on a diet high in SAFA, in comparison to those maintained on a diet high in PUFA, have significantly higher levels of mRNA coding for a number of the proteins that are important for intestinal integrity such as Tight Junction Protein ZO-1, Intestine Claudin 1, and Intestine Occludin. Furthermore, alcohol consumption further decreases the mRNA levels of most of these genes in animals fed a high-PUFA containing diet, while alcohol has no effect on levels in SAFA-fed animals. Changes in mRNA level do not necessarily mean changes in protein levels, however the same study showed an increase in intestinal permeability in mice fed PUFA and ethanol in comparison to control when measured by an ex-vivo fluorescent assay. This shows that PUFA alone can disturb the expression of proteins that maintain gut integrity, and that alcohol further diminishes integrity. In combination with a SAFA diet, however, alcohol does not affect intestinal permeability [4].

Improved gut integrity is no doubt a key aspect of the protective effects of SAFA. Increased gut integrity leads to decreased inflammatory compounds in the blood, which in turn means there will be decreased inflammatory interactions in the liver. Indeed, in comparison to animals fed alcohol and PUFA, animals fed alcohol with a SAFA diet had significantly lower levels of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-a and the marker of macrophage infiltration MCP-1 [4]. Decreased inflammation, both systemically and in the liver, is undoubtedly a key element of the protective effects of dietary SAFA.

This post is already becoming dangerously long, so without going into too much detail, it is worth mentioning that there are other mechanisms by which SAFA appear to protect against alcoholic liver disease. Increased SAFA appear to increase liver membrane resistance to oxidative stress, and also reduces fatty acid synthesis while increasing fatty acid oxidation [3]. Also, a diet high in SAFA is associated with reduced lipid peroxidation, which in turn decreases a number of elements of inflammatory cascades [5]. Finally- and this is something I will expand on in a future post- MCFAs (which are also SAFA) have a number of unique protective elements.

I realize that this post has gotten rather lengthy and has brought up a number of complex mechanisms likely well beyond the level of interest of most of my readers…

If all else fails- please consider this:

The “evidence” that saturated fats are detrimental to cardiac health is largely based on epidemiological and experimental studies that combined saturated fats with truly-problematic artificial trans-fats. Despite the permeation of the phrase “artery clogging saturated fats”, I have yet to see the evidence nor be convinced of a proposed mechanism by which saturated fats could lead to decreased coronary health.

ON THE CONTRARY…

There is significant evidence, founded in epidemiological observations, confirmed in the lab, and explored in great detail that shows that saturated fats are protective for the liver. While I have focused here on the protective effects when SAFA are combined with alcohol, they offer protection to the liver under other circumstances, such as when combined with the particularly liver-toxic pain-killer Acetaminophen [7].

Next time you eat a steak, chow down on coconut oil, or perhaps most importantly turn up your nose at all things associated with “vegetable oils” (cottonseed? soybean? Those are “vegetables”?), know that your liver appreciates your efforts!

1. Nanji, A.A. and S.W. French, Dietary factors and alcoholic cirrhosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 1986. 10(3): p. 271-3.

2. Nanji, A.A., C.L. Mendenhall, and S.W. French, Beef fat prevents alcoholic liver disease in the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 1989. 13(1): p. 15-9.

3. Ronis, M.J., S. Korourian, M. Zipperman, R. Hakkak, and T.M. Badger, Dietary saturated fat reduces alcoholic hepatotoxicity in rats by altering fatty acid metabolism and membrane composition. J Nutr, 2004. 134(4): p. 904-12.

4. Kirpich, I.A., W. Feng, Y. Wang, Y. Liu, D.F. Barker, S.S. Barve, and C.J. McClain, The type of dietary fat modulates intestinal tight junction integrity, gut permeability, and hepatic toll-like receptor expression in a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2012. 36(5): p. 835-46.

5. Nanji, A.A., K. Jokelainen, G.L. Tipoe, A. Rahemtulla, and A.J. Dannenberg, Dietary saturated fatty acids reverse inflammatory and fibrotic changes in rat liver despite continued ethanol administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2001. 299(2): p. 638-44.

6. DeMeo, M.T., E.A. Mutlu, A. Keshavarzian, and M.C. Tobin, Intestinal permeation and gastrointestinal disease. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2002. 34(4): p. 385-96.

7. Hwang, J., Y.H. Chang, J.H. Park, S.Y. Kim, H. Chung, E. Shim, and H.J. Hwang, Dietary saturated and monounsaturated fats protect against acute acetaminophen hepatotoxicity by altering fatty acid composition of liver microsomal membrane in rats. Lipids Health Dis, 2011. 10: p. 184.

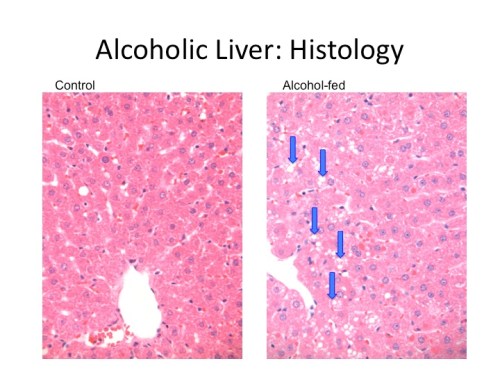

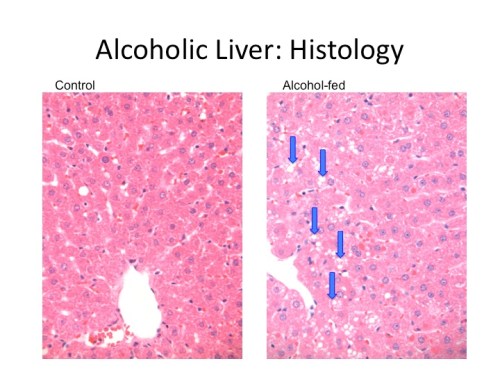

What is “Fatty Liver”? Well here’s a slide from my research showing a slice of liver from a control-fed rat on the left and an alcohol-fed rat on the right. Arrows mark macrovesicular lipid accumulations (other models can show much more impressive lipid accumulations).